Coupon giant Groupon has seen a meteoric rise, but its revenue has fallen drastically. What happened to this Wall Street star?

In 2022, the global revenue at Groupon fell to $599.09 million, coming from $3.01 billion in 2016. Groupon has been riding the wave of success since its IPO in 2011. It saw enormous growth, but eventually all came crumbling down. Groupon joined the ranks of BuzzFeed, who saw tremendous growth and interest from investors, but the profits were yet to follow.

At the time of its IPO Groupon boasted 33.74 million active customers. During its all time high, in the last quarter of 2014, Groupon had 53.9 million active customers. This number fell to 47.9 million in just two years. The internet company saw a brief recovery over 2017, but as the world entered 2018, the inevitable decline kicked in.

This might come as a surprise to those who haven’t followed Groupon actively since its inception, expecting that active customers numbers would come into a freefall as the pandemic started in the opening hours of 2020. But the decline started a few years earlier. How did Group, a Wallstreet darling, fall so hard so quickly?

Groupon’s rapid growth

In April 2011, Forbes magazine spoke with early Groupon investor Eric Lefkofsky. The investment into the coupon and cashback factory turned him into a billionaire at the age of 41, turning him into an enviable venture capitalist. In the interview he retold his time with the team at Groupon. Lefkosky has been involved in multiple start-ups such as Sprout Social, Poggled and Betterfly through his investment firm Lightbank.

Lefkofsky was tightly involved with Groupon before the appointment of its new CEO. Despite his decreasing involvement, he was still out and about with the coupon company on a daily basis. Reason being the explosive growth phase Groupon was experiencing. A scenario that went beyond the wildest imaginations of many investors. This was reflected in the company’s entry into the stock market.

In November 2011, Reuters labeled Groupon’s IPO the biggest since Google. The coupon company, who raised $700 million when listing on the Nasdaq stock exchange, saw its valuation grow to $13 billion. The company was only three years old, but already experienced a major debut. But as large as its IPO, as strong was the skepticism that the company could withstand the financial prowess of Google and Amazon.

Head of technology-focused hedge fund firm Connective Capital Management, Rob Romero, told Reuters that Groupon was expensive, noting that its $12.8 billion valuation could only be reached due to its low float, which sat at about 5 percent during its IPO. The float refers to the amount of shares a company has issued to the public. The amount of free floating shares can give an indication as to how internal shareholders can impact stock performance.

Questionable business model

The cash position and profit horizon for Groupon were still a mystery to many. The company had yet to show it would be able to turn a healthy profit in the long-term. Furthermore, Reuters pointed out that early investors would be eager to sell their stake in Groupon. Founder of IPO research and investment company IPOX Schuster, Josef Schuster, warned that post-IPO investors would be taking a gamble. Groupon stock might be an interesting choice for day-traders, but Schuster wouldn’t be in it for the long run, he added.

Schuster wasn’t the only one who raised questions about the profitability opportunities at Groupon. In May 2011, staff of the Knowledge at Wharton blog spoke with Professor of Marketing at the Wharton School, David Reibstein about the unsustainable market conditions in the discount and coupon space, which found itself in a pinch as the economy was starting a rapid cool down. Reibstein took Groupon as the primary example for a shrinking consumer segment.

Reibstien pointed out that Groupon rode the customer pooling wave thanks to the massive reach of the internet. Companies like Groupon were able to pool customers and offer discounts by using its collective bargaining power. They used the massive potential of its customer base to negotiate better prices. This wasn’t a new phenomenon, Reibstein noted, pointing toward cooperatives or franchises who used a similar approach.

Groupon was able to generate massive revenue through a fairly simple model and wherever there is easy money to be made, competitors are bound to enter the space. Reibstein cited that Groupon was fighting for market dominance with 499 competitors in its rearview mirror. While this might be the obvious reason, the selling point itself only lasts when consumers are actively looking for discounts. This demand organically decreases when the economy is set to recover, Reibstein explained.

In July 2011, in anticipation of the upcoming IPO, Professor at the Columbia Business School, Rita McGrath, pointed out additional flaws in the company’s business model. The first problem was the low barrier to entry for new customers to make use of the service, which could act as a potential obstacle for Groupon to build long lasting and profitable relationships with its users.

These effects are reinforced as customers can pay as they go. No subscription is needed to make use of the platform. The coupons meanwhile are sent to the customer by email after a successful transaction has been made, further distancing the relationship between the customer and the platform, McGrath pointed out.

The services on the platform aren’t essential in nature. While it might be a new and innovative way for customers to explore new local businesses and experiences, there’s no need to return once this need has been fulfilled. Groupon lacked the stickiness factors that ensured that users kept returning to the platform. Mason however was still very much convinced that his company would become a profit machine.

Groupon the Coupon king

In January 2012, the German news outlet Der Spiegel, spoke with Andrew Mason about the explosive growth the coupon factory Groupon had experienced just a few years after its founding. At the time of the interview, the company was valued at $12.5 billion, but behind this massive valuation, Groupon was yet to make a profit. Mason explained the company was only three years old and its investors believed there was a massive profit opportunity on the horizon.

This didn’t mean that it would be smooth sailing for the company. Just like Reuters pointed out a year prior, Der Spiegel questioned whether Groupon would be safe from competitors who could easily replicate its business model. Mason confidently explained that there were already thousands of competitors operating in the space, highlighting start-ups like Yelp, OpenTable and TravelZoo among others. While these companies have been able to easily enter the market, scaling their businesses proved difficult, he added.

The reason many of them weren’t able to topple Groupon was the complex nature of its operations. Mason noted that thousands of salespeople around the globe worked around the clock to onboard merchants and deliver a positive experience to customers. At the time of the interview, Groupon had 5,735 sales representatives and support staff. The highest amount in the company’s history.

Meanwhile, Groupon was frantically innovating its platform and laying down a strategy for the next five years. The allocation of massive resources to grow the business could be seen in the inability for Groupon to turn a profit. Even years down the line. Since its inception, the company had been generating hundreds of millions in losses. In 2009, Groupon generated $1.34 million in losses. The year after, in 2010, losses increased dramatically to $413.39 million.

The cash position stabilized, but still expenses pushed heavily on Groupon, who generated a loss of $297.76 million in 2011. By the end of 2012, revenue improved and losses were reduced to $51.03 million. In the eyes of Mason and shareholders alike this might have indicated that profits would soon follow. However, as time progressed, losses would accumulate. Over 2009 and 2012, Groupon had already accumulated over $740 million in losses.

A changing mobile landscape

In March 2013, Owen Thomas from Business Insider briefly spoke with Andrew Mason, shortly before his departure, reflecting on the changing market dynamics that Groupon had to navigate. The exchange gave a small glimpse as to how Groupon carved out a new internet segment, whilst seeing changing consumer behavior, primarily in the mobile space.

Mason noted that mobile adoption had reshaped how people discover new businesses. For Groupon this meant that 22 percent of its traffic was coming from mobile with the year prior and was set to increase to 30 to 40 percent by the end of 2013. He compared the rapidly changing market dynamic to the rise of the internet, which had spawned ecommerce giants such as Amazon and enabled online video streaming. Mobile had the same effect on local businesses.

As the founder, Mason prided himself that Groupon was able to build a bridge between small and medium sized businesses, acting as the funnel, allowing consumers to discover new experiences through online coupons. The massive traffic amounts gave Groupon unique insights into consumer behavior, through which it could find the right customers and forward them to the local businesses effectively.

The data used today was still only the tip of the ice and as time would progress new inventive opportunities would be unlocked to further develop a vibrant local ecommerce ecosystem. However, even as this landscape was starting to form, Groupon had to find the right balance between scaling and maintaining a healthy relationship with the connected businesses.

Mason pointed out that the Groupon team had figured out how it could scale sustainability, whilst ensuring that local businesses wouldn’t be overrun by new customers, which in turn would do more harm than good. At time of the interview, Mason was still convinced that Groupon would see strong growth and the platform would further evolve. In hindsight however, this growth would only last for another five years upon which the foundations of the company would come crumbing down.

Turmoil at Groupon

In March 2013, Groupon fired co-founder Mason. Mason shared his internal memo with Reuters where he noted that his firing was a result of poor operating results, including missing its stock price target. Reuters commented that Kal Raman, who was appointed CEO in November 2012, could be an available candidate for the open seat. Reuters predictions weren’t far off, as shortly after Groupon announced Kal Raman would become the Chief Operating Officer at Groupon.

Analyst at Macquarie Research, Tom White, told Reuters that Groupon had grown into a large and complex organization, which would require an executive who would be able to navigate these treacherous conditions or reduce the complexity. Chief investment officer at AlphaOne Capital, Dan Niles, added that the new CEO would face a tough road ahead, demanding strong willpower.

The news about Mason’s departure from the company might have been more a result of his quirky and irreverent nature and not so much the business results itself, argued Management Professor, Timothy Judge from the University of Notre Dame, Indiana in March 2013. Judge pointed toward former CEO at American department store chain JCPenney, Ron Johnson, who was able to maintain his role after the largest quarterly losses in the company’s history.

Judge added that Groupon was overvalued during its IPO, which put more pressure on the board and investors to find a scapegoat. This could’ve been Mason, he commented. A leader who had no credentials nor previous corporate experience couldn’t possibly be fit to steer the company in the right direction and meet its own ambitious valuation. Whether this could’ve been prevented, we will never know, but little changed under its new leadership.

Costs spiraling out of control

Groupon felt competition intensify and its executive teams believed that user acquisition would need to accelerate in order for the company to turn a profit. This can be witnessed in its relentless marketing spending which started to grow exponentially after Mason’s lay-off. In 2013, Groupon spent $194 million on marketing, the following year this figure had increased to $227.86 million.

This is a minor change, but marketing expenditure started to balloon over 2016, where the company spent $352.18 million on marketing.The spending rise of 2016, wasn’t the last attempt of executives to turn the ship around. Marketing expenditure peaked in 2017, where it spent a record $400.92 million on marketing. These costs gradually decreased and fell dramatically over the course of the global pandemic.

Marketing expenditure is a double edged sword. It can unlock new growth opportunities, especially when a company has already established profitability through a sustainable business model. However, marketing costs can also push heavily on a company’s balance sheet when it’s still figuring out a healthy business model. These effects are compounded when customer churn is high and a constant stream of new customers is necessary to increase revenue. This rings especially true for companies operating in the meal kit delivery service like HelloFresh.

Stabilizing the balance sheet

In order to bring costs down, Groupon started to slash its workforce. In September 2015, the company announced it would lay-off 10 percent of its staff, or 1,100 employees. CNN commented that cuts would primarily be made across its customer service department and its so-called “Deal Factory”, who is tasked with maintaining merchant relationships and generating and researching sales leads.

Along with the lay-offs, Groupon would be shutting down operations in Morocco, Panana, Puerto Rico, Taiwan, Thailand among others. It had already retreated from Greece and Turkey. In the statement referenced by CNN, the company explained that it had ambitions to create a unified global business. However, as Groupon evolved it had to evaluate and reconsider its global presence and the investment required to uphold it.

In May 2016, the company announced it would lay off another 30 employees at its customer service department. The announcement came in the wake of the newly appointed chief financial officer and its recent earnings report. The lay-off figures were substantially higher than its previous workforce reduction efforts, but nonetheless served as a strong indicator that the company was having trouble stabilizing its bottom line.

Accelerating lay-offs

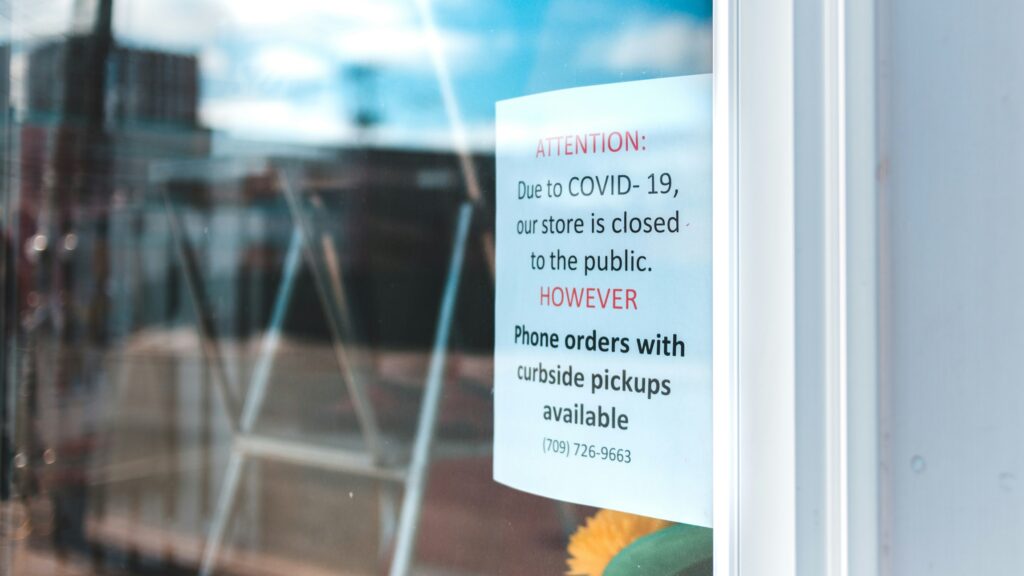

The problems at the company spiraled out of control as the world entered lockdown and businesses around the globe were forced to close their doors. In April 2020, Groupon said it would be laying-off 1,400 employees as part of a restructuring program. The company expected it would lay-off another 1,400 employees by summer 2021, Chicago Business cited from a securities filing. The lay-offs would translate into a workforce reduction of 44 percent. The first round of lay-offs would target its global workforce.

The massive workforce reductions came after businesses had to shut down due to pandemic restrictions. Coupon sales already started to fall at the beginning of the year, but the pandemic accelerated the decline, with Groupon estimating that coupon sales would fall by 70 percent over the month of April. In order to secure operations, it had borrowed $150 million. The company said it would scale down its Goods program, which at the time accounted for 50 percent of its revenue.

Two years later, in August 2022, Groupon announced it would lay off 500 employees to further reduce costs and improve productivity. The company has also put efforts into automating some of its business operations, such as self-service merchants acquisition capabilities. The company would reduce office space, that would be better tailored to hybrid working. CEO at Groupon, Kedar Deshpande, explained to Techcrunch that cost reductions were necessary to stabilize business performance, which were below expectations.

The available funds would be allocated to marketing efforts to drive customer acquisition. Desphande wrote to its employees that the company would refocus on mission-critical activities and pivot toward external support. Additionally, the coupon platform would explore pathways to reduce cloud infrastructure and support functions. In order to accelerate cost reductions, its Australia Goods segment would be closed down.

A few months later, in January 2023, the company said it would lay-off another 500 employees. The workforce reduction effort is part of the second phase of Groupon’s restructuring plan, which was revealed in August last year, CBS News added. A few months later, in March 2023, Groupon announced that board member and Co-Founder of Pale Fire Capital, Dusan Senkypl, would become the new CEO, replacing Kader Deshpande.

In May 2023, Groupon warned that it would run out of cash in the next 12 months. The deals platform kept losing money, the company said. Operating losses kept pushing on the balance sheet, which raised concerns with its executive team whether it would meet its obligations. To reduce its costs wherever possible, it terminated the lease on its headquarters in Chicago two years before the end of the contract. The contract termination cost the company $9.6 million, but would free up funds to secure operations.

The fall of Groupon

Looking back on the brief history of Groupon, we can see that it became a victim of its own success. The company saw rapid growth just a few years in and investors were confident the platform would become a money printing machine. Groupon started expanding aggressively. Entering market after market in rapid succession. Priding itself with its massive global footprint. Its workforce grew exponentially. The company’s IPO was one of the largest in Wall Street history, second only to Google. But experts wondered how the company would ever turn a profit.

The platform had no active relationship with its customers. Hence, its added value was negligible. Mason, the flamboyant CEO meanwhile, was considered an improper fit according to its board. The co-founder had to part ways with the company he helped build. One might think that the executive team would now set in a more conservative path that would ease growth and redefine the customer and merchant experience. But the opposite happened.

Groupon ramped up marketing spending like never before. Spending hundreds of millions to attract new customers and increase transactions as fast as possible. We might speculate the executive team was looking for avenues to meet its own, unrealistic, growth expectations. Hoping to meet the valuation it once had. In actuality, operational costs only increased, further pushing the company into the red, leaving it vulnerable for unexpected macro-economic forces.

These forces came quickly and at an unprecedented scale never seen in modern economic history. The world went into a complete shutdown. The nail in the coffin for a company so heavily dependent on local businesses and their interactions with customers. Groupon’s financial situation deteriorated quickly. It started to frantically lay-off workers. Thousands of employees lost their jobs. Little could be done to save it from defaulting on its obligations.

Groupon is still around at the time of writing, but it has become a shadow of its former self. Just like BuzzFeed, its executives were overly confident that their business was unique. Invincible. Irreplaceable. Sentiments can change, however. Without a strong customer relationship, companies are destined to fail.